The Go programming language (also known as Golang) has gained popularity during the last few years among malware developers . This can certainly be explained by the relative simplicity of the language, and the cross-compilation ability of its compiler, allowing multi-platform malware development without too much effort.

In this blog post, we dive into Golang executables reverse engineering, and present a Python extension for JEB decompiler to ease Golang analysis; here is the table of content:

- Golang Basics for Reverse Engineers

- Making JEB Great for Golang

- Use-Case: Analysis of StealthWorker Malware

The JEB Python script presented in this blog can be found on our GitHub page. Make sure to update JEB to version 3.7+ before running it.

Disclaimer: the analysis in this blog post refers to the current Golang version (1.13) and part of it might become outdated with future releases.

Golang Basics for Reverse Engineers

Feel free to skip this part if you’re already familiar with Golang reverse engineering.

Let’s start with some facts that reverse engineers might find interesting to know before analyzing their first Golang executable.

1. Golang is an open-source language with a pretty active development community. The language was originally created at Google around 2007, and version 1.0 was released in March 2012. Since then, two major versions are released each year.

2. Golang has a long lineage: in particular many low-level implementation choices — some would say oddities — in Golang can be traced back to Plan9, a distributed operating system on which some Golang creators were previously working.

3. Golang has been designed for concurrency, in particular by providing so-called “goroutines“, which are lightweight threads executing concurrently (but not necessarily in parallel).

Developers can start a new goroutine simply by prefixing a function call by go. A new goroutine will then start executing the function, while the caller goroutine returns and continues its execution concurrently with the callee. Let’s illustrate that with the following Golang program:

func myDummyFunc(){

time.Sleep(1 * time.Second)

fmt.Println("dummyFunc executed")

}

func main(){

myDummyFunc() // normal call

fmt.Println("1 - back in main")

go myDummyFunc() // !! goroutine call

fmt.Println("2 - back in main")

time.Sleep(3 * time.Second)

}

Here, myDummyFunc() is called once normally, and then as a goroutine. Compiling and executing this program results in the following output:

dummyFunc executed

1 - back in main

2 - back in main

dummyFunc executedNotice how the execution was back in main() before executing the second call to dummyFunc().

Implementation-wise, many goroutines can be executed on a single operating system thread. Golang runtime takes care of switching goroutines, e.g. whenever one executes a blocking system call. According to the official documentation “It is practical to create hundreds of thousands of goroutines in the same address space“.

What makes goroutines so “cheap” to create is that they start with a very limited stack space (2048 bytes — since Golang 1.4), which will be increased when needed.

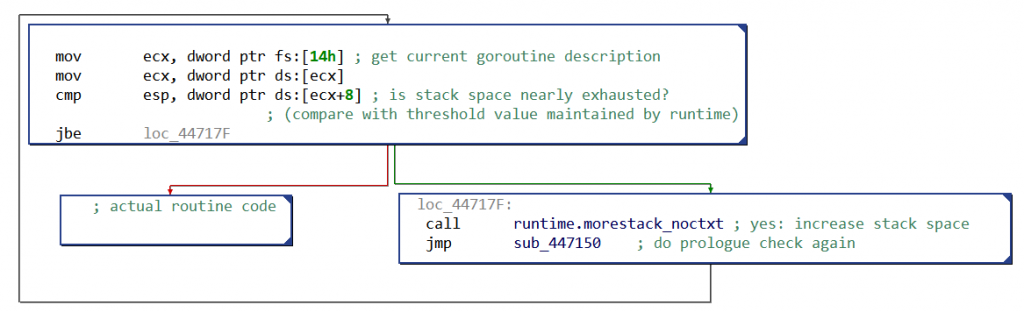

One of the noticeable consequence for reverse engineers is that native routines (almost) all start with the same prologue. Its purpose is to check if the current goroutine’s stack is large enough, as can be seen in the following CFG:

When the stack space is nearly exhausted, more space will be allocated — actually, the stack will be copied somewhere with enough free space. This particular prologue is present only in routines with local variables.

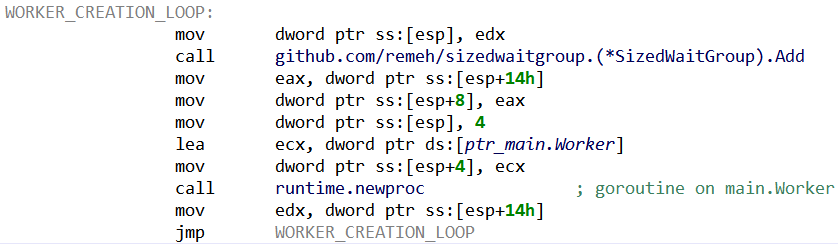

How to distinguish a goroutine call from a “normal” call when analyzing a binary? Goroutine calls are implemented by calling runtime.newproc, which takes in input the address of the native routine to call, the size of its arguments, and then the actual routine’s arguments.

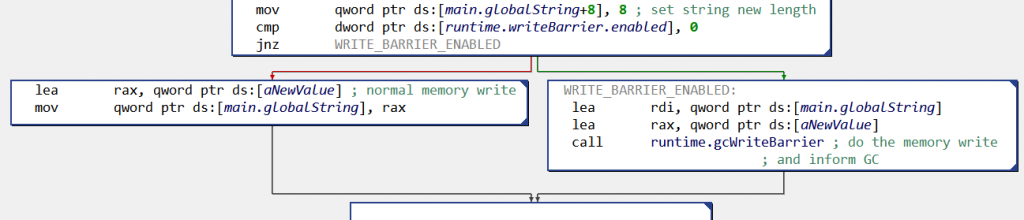

4. Golang has a concurrent garbage collector (GC): Golang’s GC can free memory while other goroutines are modifying it.

Roughly speaking, when the GC is freeing memory, goroutines report to it all their memory writes — to prevent concurrent memory modifications to be missed by the current freeing phase. Implementation-wise, when the GC is in the process of marking used memory, all memory writes pass through a “write barrier“, which performs the write and informs the GC.

For reverse engineers this can result in particularly convoluted control flow graphs (CFG). For example, here is the CFG when a global variable globalString is set to newValue:

globalString (x86 CFG):before doing the memory write, the code checks if the write barrier is activated,

and if yes calls

runtime.gcWriteBarrier()Not all memory writes are monitored in that manner; the rules for write barriers’ insertion are described in mbarrier.go.

5. Golang comes with a custom compiler tool chain (parser, compiler, assembler, linker), all implemented in Golang. 1 2

From a developer’s perspective, it means that once Go is installed on a machine, one can compiled for any supported platform (making Golang a language of choice for IoT malware developers). Examples of supported platforms include Windows x64, Linux ARM and Linux MIPS (see “valid combinations of $GOOS and $GOARCH“).

From a reverse engineer’s perspective, the custom Go compiler toolchain means Golang binaries sometimes come with “exotic” features (which therefore can give a hard time to reverse engineering tools).

For example, symbols in Golang Windows executables are implemented using the COFF symbol table (while officially “COFF debugging information [for executable] is deprecated“). The Golang COFF symbol implementation is pretty liberal: symbols’ type is set to a default value — i.e. there is no clear distinction between code and data.

As another example, Windows PE read-only data section “.rdata” has been defined as executable in past Go versions.

Interestingly, Golang compiler internally uses pseudo assembly instructions (with architecture-specific registers). For example, here is a snippet of pseudo-code for ARM (operands are ordered with source first):

MOVW $go.string."hello, world\n"(SB), R0

MOVW R0, 4(R13)

MOVW $13, R0

MOVW R0, 8(R13)

CALL "".dummyFunc(SB)

MOVW.P 16(R13), R15

These pseudo-instructions could not be understood by a classic ARM assembler (e.g. there is no CALL instruction on ARM). Here are the disassembled ARM instructions from the corresponding binary:

LDR R0, #451404h // "hello, world\n" address

STR R0, [SP, #4]

MOV R0, #13

STR R0, [SP, #8]

BL main.dummyFunc

LDR PC, [SP], #16

Notice how the same pseudo-instruction MOVW got converted either as STR or MOV machine instructions. The use of pseudo-assembly comes from Plan9, and allows Golang assembler parser to easily handle all architectures: the only architecture-specific step is the selection of machine instructions (more details here).

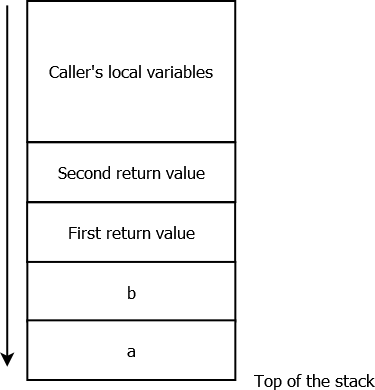

6. Golang uses by default a stack-only calling convention.

Let’s illustrate that with the following diagram, showing the stack’s state when a routine with two integer parameters a and b, and two return values — declared in Go as “func myRoutine(a int, b int) (int, int)” — is called:

It is the caller’s responsibilities to reserve space for the callees’ parameters and returned values, and to free it later on.

Note that Golang’s calling convention situation might soon change: since version 1.12, several calling conventions can coexist — the stack-only calling convention remaining the default one for backward compatibility reasons.

7. Golang executables are usually statically-linked, i.e. do not rely on external dependencies 3. In particular they embed a pretty large runtime environment. Consequently, Golang binaries tend to be large: for example, a “hello world” program compiled with Golang 1.13 is around 1.5MB with its symbols stripped.

8. Golang executables embed lots of symbolic information:

- Debug symbols, implemented as DWARF symbols. These can be stripped at compilation time (command-line option

-ldflags "-w") . - Classic symbols for each executable file format (PE/ELF/Mach-O). These can be stripped at compilation time (command-line option

-ldflags "-s"). - Go-specific metadata, including for example all functions’ entry points and names, and complete type information. These metadata cannot (easily) be stripped, because Golang runtime needs them: for example, functions’ information are needed to walk the stack for errors handling or for garbage collection, while types information serve for runtime type checks.

Of course, Go-specific metadata are very good news for reverse engineers, and parsing these will be one of the purpose of the JEB’s Python extension described in this blog post.

Making JEB Great for Golang

Current Status

What happens when opening a Golang executable in JEB? Let’s start from the usual “hello world” example:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

fmt.Printf("hello, world\n")

}

If we compile it for as a Windows x64 PE file, and open it in JEB, we can notice that its code has only been partially disassembled. Unexplored memory areas can indeed be seen next to code areas in the native navigation bar (right-side of the screen by default):

(blue is code, green is data, grey represents area without any code or data)

We can confirm that the grey areas surrounding the blue areas are code, by manually disassembling them (hotkey ‘C’ by default).

Why did JEB disassembler miss this code? As can be seen in the Notifications window, the disassembler used a CONSERVATIVE strategy, meaning that it only followed safe control flow relationships (i.e. branches with known targets) 4.

Because Go runtime calls most native routines indirectly, in particular when creating goroutines, JEB disassembler finds little reliable control flow relationships, explaining why some code areas remain unexplored.

Before going on, let’s take a look at the corresponding Linux executable, which we can obtain simply by setting environment variable $GOOS to linux before compiling. Opening the resulting ELF file in JEB brings us in a more positive situation:

(blue is code, green is data, grey represents area without any code or data)

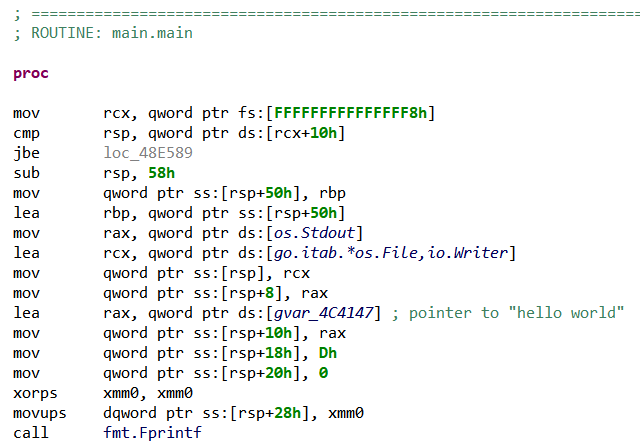

Due to the use by default of AGGRESSIVE strategy for disassembling ELF files, JEB disassembler found the whole code area (all code sections were linearly disassembled). In particular this time we can see our main routine, dubbed main.main by the compiler:

Are data mixed with code in Golang executables? If yes, that would make AGGRESSIVE disassembly a risky strategy. At this moment (version 1.13 with default Go compiler), this does not seem to be the case:

– Data are explicitly stored in different sections than code, on PE and ELF.

– Switch statements are not implemented with jumptables — a common case of data mixed with code, e.g. in Visual Studio or GCC ARM. Note that Golang provides several switch-like statements, as the select statement or the type switch statement.

As anything Golang related, the situation might change in future releases (for example, there is still an open discussion to implement jumptables for switch).

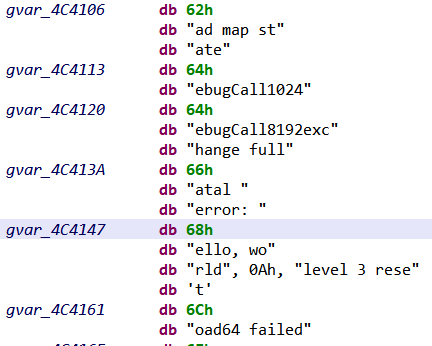

Yet, there is still something problematic in our ELF disassembly: the “hello world” string was not properly defined. Following the reference made by LEA instruction in the code, we reach a memory area where many strings have indeed been misrepresented as 1-byte data items:

Now that we have a better idea of JEB’s current status, we are going to explain how we extended it with a Python script to ease Golang analysis.

Finding and Naming Routines

The first problem on our road is the incomplete control flow, specially on Windows executables. At first, it might seem that PE files disassembly could be improved simply by setting disassembler’s strategy to AGGRESSIVE, exactly as for ELF files. While it might be an acceptable quick solution, we can actually improve the control flow in a much safer way by parsing Go metadata.

Parsing “Pc Line Table”

Since version 1.2, Golang executables embed a structure called “pc line table”, also known as pclntab. Once again, this structure (and its name) is an heritage from Plan9, where its original purpose was to associate a program counter value (“pc”) to another value (e.g. a line number in the source code).

The structure has evolved, and now contains a function symbol table, which stores in particular the entry points and names of all routines defined in the binary. The Golang runtime uses it in particular for stack unwinding, call stack printing and garbage collection.

In others words, pclntab cannot be easily stripped from a binary, and provide us a reliable way to improve our disassembler’s control flow!

First, our script locates pclntab structure (refer to locatePclntab() for the details):

# non-stripped binary: use symbol

if findSymbolByName(golangAnalyzer.codeContainerUnit, 'runtime.pclntab') != None:

pclntabAddress = findSymbolByName(..., 'runtime.pclntab')

# stripped binary

else:

# PE: brute force search in .rdata. or in all binary if section not present

if [...].getFormatType() == WellKnownUnitTypes.typeWinPe

[...]

# ELF: .gopclntab section if present, otherwise brute force search

elif [...].getFormatType() == WellKnownUnitTypes.typeLinuxElf:

[...]

On stripped binaries (i.e. without classic symbols), we search memory for the magic constant 0xFFFFFFFB starting pclntab, and then runs some checks on the possible fields. Note that it is usually easier to parse Golang ELF files, as important runtime structures are stored in distinct sections.

Second, we parse pclntab and use its function symbol table to disassemble all functions and rename them:

[...]

# enqueue function entry points from pclntab and register their names as labels

for myFunc in pclntab.functionSymbolTable.values():

nativeCodeAnalyzer.enqueuePointerForAnalysis(EntryPointDescription(myFunc.startPC), INativeCodeAnalyzer.PERMISSION_FORCEFUL)

if rename:

labelManager.setLabel(myFunc.startPC, myFunc.name, True, True, False)

# re-run disassembler with the enqueued entry points

self.nativeCodeAnalyzer.analyze()

Running this on our original PE file allows to discover all routines, and gives the following navigation bar:

(blue is code, green is data, grey represents area without any code or data)

Interestingly, a few Golang’s runtime routines provide hints about the machine used to compile the binary, for example:

– runtime.schedinit(): references Go’s build version. Knowing the exact version allows to investigate possible script parsing failures (as some internal structures might change depending on Go’s version).

– runtime.GOROOT(): references Go’s installation folder used during compilation. This might be useful for malware tracking.

These routines are present only if the rest of the code relies on them. If it is the case, FunctionsFinder module highlights them in JEB’s console, and the user can then examine them.

The Remaining Unnamed Routines

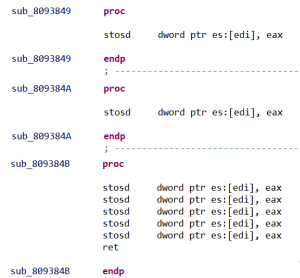

Plot twist! A few routines found by the disassembler remain nameless even after FunctionsFinder module parsed pclntab structure. All these routines are adjacent in memory and composed of the same instructions, for example:

Long story short, these routines are made for zeroing or copying memory blobs, and are part of two large routines respectively named duff_zero and duff_copy.

These large routines are Duff’s devices made for zeroing/copying memory. They are generated as long unrolled loops of machine instructions. Depending on how many bytes need to be copied/zeroed the compiler will call directly on a particular instruction. For each of these calls, a nameless routine will then be created by the disassembler.

DuffDevicesFinder module identifies such routines with pattern matching on assembly instructions. By counting the number of instructions, it then renames them duff_zero_N/duff_copy_N, with N the number of bytes zeroed/copied.

Source Files

Interestingly, pclntab structure also stores original source files‘ paths. This supports various Golang’s runtime features, like printing meaningful stack traces, or providing information on callers from a callee (see runtime.Caller()). Here is an example of a stack trace obtained after a panic():

PANIC

goroutine 1 [running]:

main.main()

C:/Users/[REDACTED]/go/src/hello_panic/hello_panic.go:4 +0x40The script extracts the list of source files and print them in logs.

Strings Recovery

The second problem we initially encountered in JEB was the badly defined strings.

What Is a String?

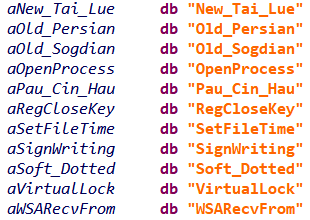

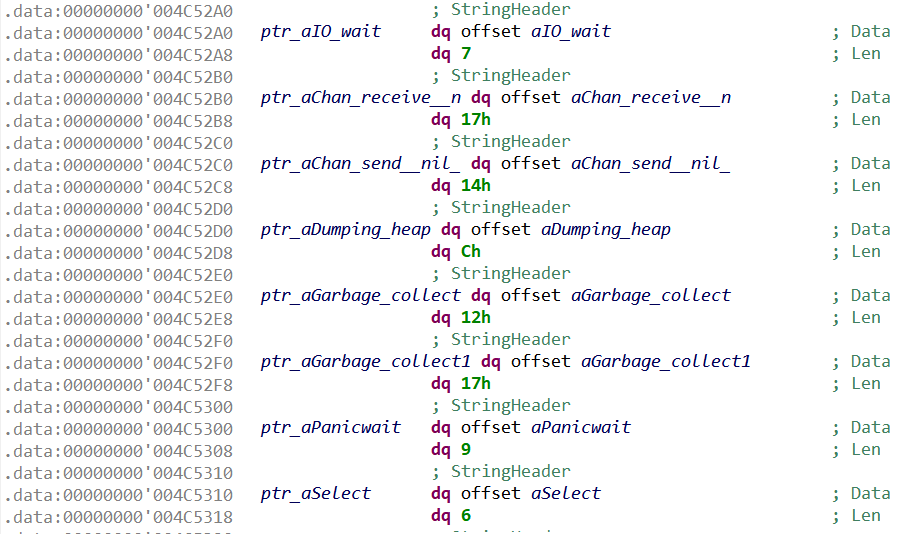

Golang’s strings are stored at runtime in a particular structure called StringHeader with two fields:

type StringHeader struct {

Data uintptr // string value

Len int // string size

}

The string’s characters (pointed by the Data field) are stored in data sections of the executables, as a series of UTF-8 encoded characters without null-terminators.

Dynamic Allocation

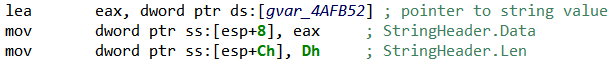

StringHeader structures can be built dynamically, in particular when the string is local to a routine. For example:

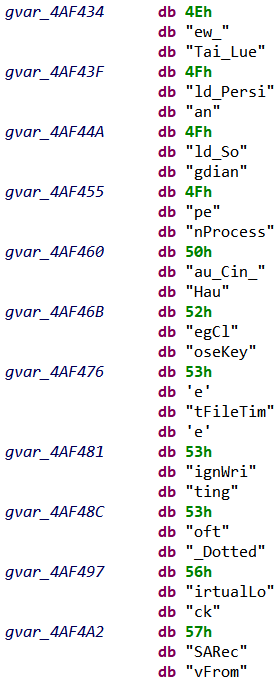

StringHeader instantiation in x86By default JEB disassembler defines a 1-byte data item (gvar_4AFB52 in previous picture) for the string value, rather than a proper string, because:

- As the string value is referenced only by

LEAinstruction, without any hints on the data type (LEAis just loading an “address”), the disassembler cannot type the pointed data accordingly. - The string value does not end with a null-terminator, making JEB’s standard strings identification algorithms unable to determine the string’s length when scanning memory.

To find these strings, StringsBuilder module searches for the particular assembly instructions usually used for instantiating StringHeader structures (for x86/x64, ARM and MIPS architectures). We can then properly define a string by fetching its size from the assembly instructions. Here is an example of recovered strings:

Before strings recovery

After strings recovery

Of course, this heuristic will fail if different assembly instructions are employed to instantiate StringHeader structures in future Golang compiler release (such change happened in the past, e.g. x86 instructions changed with Golang 1.8).

Static Allocation

StringHeader can also be statically allocated, for example for global variables; in this case the complete structure is stored in the executable. The code referencing such strings employs many different instructions, making pattern matching not suitable.

To find these strings, we scan data sections for possible StringHeader structures (i.e. a Data field pointing to a printable string of size Len). Here is an example of recovered structures:

StringHeaderThe script employs two additional final heuristics, which scan memory for printable strings located between two already-defined strings. This allows to recover strings missed by previous heuristics.

When a small local string is used for comparison only, no StringHeader structure gets allocated. The string comparison is done directly by machine instructions; for example, CMP [EAX], 0x64636261 to compare with “abcd” on x86.

Types Recovery

Now that we extended JEB to handle the “basics” of Golang analysis, we can turn ourselves to what makes Golang-specific metadata particularly interesting: types.

Golang executables indeed embed descriptions for all types manipulated in the binary, including in particular those defined by developers.

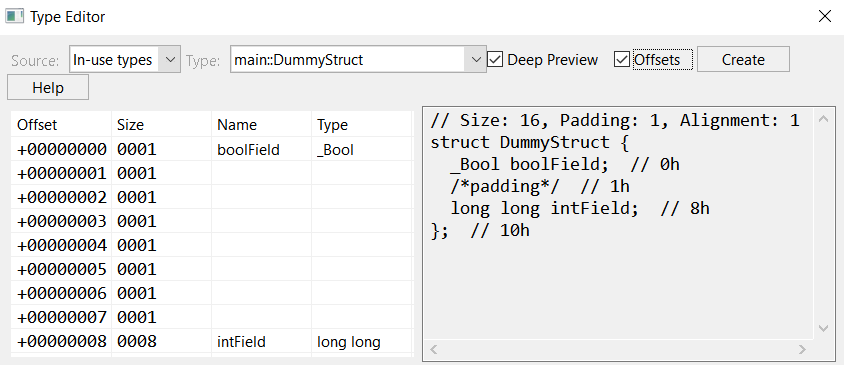

To illustrate that, let’s compile the following Go program, which defines a Struct (Golang’s replacement for classes) with two fields:

package main

type DummyStruct struct{

boolField bool

intField int

}

func dummyFunc(s DummyStruct) int{

return 13 * s.intField

}

func main(){

s := DummyStruct{boolField: true, intField:37}

t := dummyFunc(s)

t += 1

}

Now, if we compile this source code as a stripped x64 executable, and analyze it with TypesBuilder module, the following structure will be reconstructed:

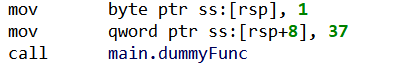

TypesBuilder, as seen in JEB’s type editorNot only did we get the structure and its fields’ original names, but we also retrieved the structure’s exact memory layout, including the padding inserted by the compiler to align fields. We can confirm DummyStruct‘s layout by looking at its initialization code in main():

DummyStruct initialization: intField starts at offset 8, as extracted from type information Why So Much Information?

Before explaining how TypesBuilder parses types information, let’s first understand why these information are needed at all. Here are a few Golang features that rely on types at runtime:

- Dynamic memory allocation, usually through a call to

runtime.newobject(), which takes in input the description of the type to be allocated - Dynamic type checking, with statements like type assertions or type switches. Roughly speaking, two types will be considered equals if they have the same type descriptions.

- Reflection, through the built-in package

reflect, which allows to manipulate objects of unknown types from their type descriptions

Golang type descriptions can be considered akin to C++ Run-Time Type Information, except that there is no easy way to prevent their generation by the compiler. In particular, even when not using reflection, types descriptors remain present.

For reverse engineers, this is another very good news: knowing types (and their names) will help understanding the code’s purpose.

Of course, it is certainly doable to obfuscate types, for example by giving them meaningless names at compilation. We did not find any malware using such technique.

What Is A Type?

In Golang each type has an associated Kind, which can take one the following values:

const (

Invalid Kind = iota

Bool

Int

Int8

Int16

Int32

Int64

Uint

Uint8

Uint16

Uint32

Uint64

Uintptr

Float32

Float64

Complex64

Complex128

Array

Chan

Func

Interface

Map

Ptr

Slice

String

Struct

UnsafePointer

)

Alongside types usually seen in programming languages (integers, strings, boolean, maps, etc), one can notice some Golang-specific types:

- Array: fixed-size array

- Slice: variable-size view of an Array

- Func: functions; Golang’s functions are first-class citizens (for example, they can be passed as arguments)

- Chan: communication channels for goroutines

- Struct: collection of fields, Golang’s replacement for classes

- Interface: collection of methods, implemented by Structs

The type’s kind is the type’s “category”; what identifies the type is its complete description, which is stored in the following rtype structure:

type rtype struct {

size uintptr

ptrdata uintptr // number of bytes in the type that can contain pointers

hash uint32 // hash of type; avoids computation in hash tables

tflag tflag // extra type information flags

align uint8 // alignment of variable with this type

fieldAlign uint8 // alignment of struct field with this type

kind uint8 // enumeration for C

alg *typeAlg // algorithm table

gcdata *byte // garbage collection data

str nameOff // string form

ptrToThis typeOff // type for pointer to this type, may be zero

}

The type’s name is part of its description (str field). This means that, for example, one could define an alternate integer type with type myInt int, and myInt and int would then be distinct types (with distinct type descriptors, each of Int kind). In particular, assigning a variable of type myInt to a variable of type int would necessitate an explicit cast.

The rtype structure only contains general information, and for non-primary types (Struct, Array, Map,…) it is actually embedded into another structure (as the first field), whose remaining fields provides type-specific information.

For example, here is strucType, the type descriptor for types with Struct kind:

type structType struct {

rtype

pkgPath name

fields []structField

}

Here, we have in particular a slice of structField, another structure describing the structure fields’ types and layout.

Finally, types can have methods defined on them: a method is a function with a special argument, called the receiver, which describes the type on which the methods applies. For example, here is a method on MyStruct structure (notice receiver’s name after func):

func (myStruct MyStruct) method1() int{

...

}

Where are methods’ types stored? Into yet another structure called uncommonType, which is appended to the receiver’s type descriptor. In other words, a structure with methods will be described by the following structure:

type UncommonStructType struct {

rtype

structType

uncommonType

}

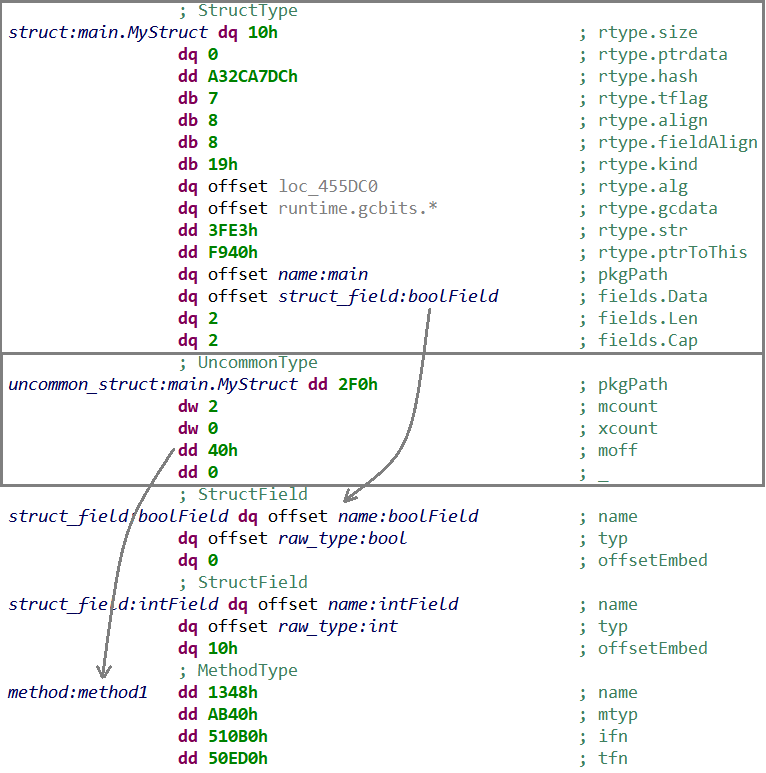

Here is an example of such structure, as seen in JEB after running TypesBuilder module:

StrucType (with embedded rtype, and referencing StructField),

followed by UncommonType (referencing MethodType)

Parsing type descriptors can therefore be done by starting from rtype (present for all types), and adding wrapper structures around it, if needed. Properly renaming type descriptors in memory greatly helps the analysis, as these descriptors are passed as arguments to many runtime routines (as we will see in StealthWorker’s malware analysis).

The final step is to transform the type descriptors into the actual types — for example, translating a structType into the memory representation of the corresponding structure –, which can then be imported in JEB types. For now, TypesBuilder do this final import step for named structures only.

Describing in details all Golang’s type descriptors is out-of-scope for this blog. Refer to TypesBuilder module for gory details.

Locating Type Descriptors

The last question we have to examine is how to actually locate type descriptors in Golang binaries. This starts with a structure called moduledata, whose purpose is to “record information about the layout of the executable“:

type moduledata struct {

pclntable []byte

ftab []functab

filetab []uint32

findfunctab uintptr

minpc, maxpc uintptr

text, etext uintptr

noptrdata, enoptrdata uintptr

data, edata uintptr

bss, ebss uintptr

noptrbss, enoptrbss uintptr

end, gcdata, gcbss uintptr

types, etypes uintptr

textsectmap []textsect

typelinks []int32 // offsets from types

itablinks []*itab

[...REDACTED...]

}

This structure defines in particular a range of memory dedicated to storing type information (from types to etypes). Then, typelink field stores offsets in the range where type descriptors begin.

So first we locate moduledata, either from a specific symbol for non-stripped binaries, or through a brute-force search. For that, we search for the address of pclntab previously found (first moduledata field), and then apply some checks on its fields.

Second, we start the actual parsing of the types range, which is a recursive process as some types reference others types, during which we apply the type descriptors’ structures.

There is no backward compatibility requirement on runtime’s internal structures — as Golang executables embed their own runtime. In particular, moduledata and type descriptions are not guaranteed to stay backward compatible with older Golang release (and they were already largely modified since their inception).

In others words, TypesBuilder module’s current implementation might become outdated in future Golang releases (and might not properly work on older versions).

Use-Case: StealthWorker

We are now going to dig into a malware dubbed StealthWorker. This malware infects Linux/Windows machines, and mainly attempts to brute-force web platforms, such as WordPress, phpMyAdmin or Joomla. Interestingly, StealthWorker heavily relies on concurrency, making it a target of choice for a first analysis.

The sample we will be analyzing is a x86 Linux version of StealthWorker, version 3.02, whose symbols have been stripped (SHA1: 42ec52678aeac0ddf583ca36277c0cf8ee1fc680)

Reconnaissance

Here is JEB’s console after disassembling the sample and running the script with all modules activated (FunctionsFinder, StringsBuilder, TypesBuilder, DuffDevicesFinder, PointerAnalyzer):

>>> Golang Analyzer <<<

> pclntab parsed (0x84B79C0)

> first module data parsed (0x870EB20)

> FunctionsFinder: 9528 function entry points enqueued (and renamed)

> FunctionsFinder: running disassembler... OK

> point of interest: routine runtime.GOROOT (0x804e8b0): references Go root path of developer's machine (sys.DefaultGoroot)

> point of interest: routine runtime.schedinit (0x8070e40): references Go version (sys.TheVersion)

> StringsBuilder: building strings... OK (4939 built strings)

> TypesBuilder: reconstructing types... OK (5128 parsed types - 812 types imported to JEB - see logs)

> DuffDevicesFinder: finding memory zero/copy routines... OK (93 routines identified)

> PointerAnalyzer: 5588 pointers renamed

> see logs (C:\[REDACTED]\log.txt)Let’s start with some reconnaissance work:

- The binary was compiled with Go version 1.11.4 (referenced in

runtime.schedinit‘s code, as mentioned by the script’s output) - Go’s root path on developer’s machine is

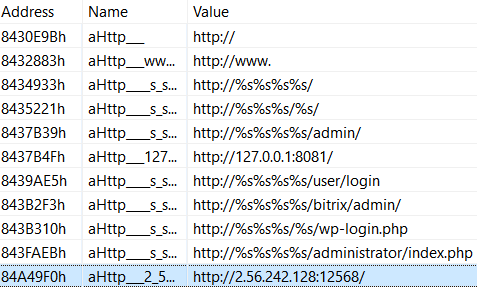

/usr/local/go(referenced byruntime.GOROOT‘s code) - Now, let’s turn to the reconstructed strings; there are too many to draw useful conclusions at this point, but at least we got an interesting IP address (spoiler alert: that’s the C&C’s address):

as seen in JEB after running the script

- More interestingly, the list of source files extracted from

pclntab(outputted in the script’slog.txt) shows a modular architecture:

> /home/user/go/src/AutorunDropper/Autorun_linux.go

> /home/user/go/src/Check_double_run/Checker_linux.go

> /home/user/go/src/Cloud_Checker/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerAdminFinder/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerBackup_finder/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerBitrix_brut/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerBitrix_check/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerCpanel_brut/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerCpanel_check/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerDrupal_brut/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerDrupal_check/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerFTP_brut/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerFTP_check/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerHtpasswd_brut/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerHtpasswd_check/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerJoomla_brut/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerJoomla_check/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerMagento_brut/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerMagento_check/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerMysql_brut/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerOpencart_brut/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerOpencart_check/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerPMA_brut/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerPMA_check/WorkerPMA_check.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerPostgres_brut/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerSSH_brut/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerWHM_brut/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerWHM_check/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerWP_brut/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/WorkerWP_check/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/Worker_WpInstall_finder/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/Worker_wpMagOcart/main.go

> /home/user/go/src/StealthWorker/main.goEach main.go corresponds to a Go package, and its quite obvious from the paths that each of them targets a specific web platform. Moreover, there seems to be mainly two types of packages: WorkerTARGET_brut, and WorkerTARGET_check.

There are no information regarding the time of compilation in Golang executables. In particular executables’ timestamps have been set to a fixed value at compilation, in order to always generate the same executable from a given input.

- Let’s dig a bit further by looking at

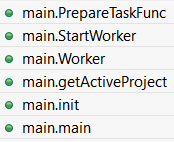

mainpackage, which is where execution begins; here are its routines with pretty informative names:

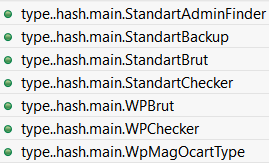

Additionally there is a series of type..hash* and type..eq* methods for main package:

These methods are automatically generated for types equality and hashing, and therefore their presence indicates that non-trivial custom types are used in main package (as we will see below).

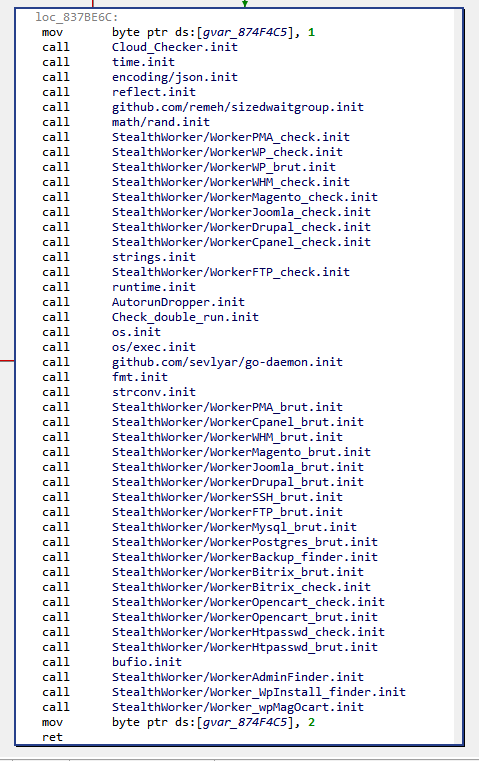

We can also examine main.init() routine. The init() routine is generated for each package by Golang’s compiler to initialize others packages that this package relies on, and the package’s global variables:

Along the previously seen packages, one can notice some interesting custom packages:

- github.com/remeh/sizedwaitgroup: a re-implementation of Golang’s WaitGroup — a mechanism to wait for goroutines termination –, but with a limit in the amount of goroutines started concurrently. As we will see, StealthWorker’s developer takes special care to not overload the infected machine.

- github.com/sevlyar/go-daemon: a library to write daemon processes in Go.

Golang packages’ paths are part of a global namespace, and it is considered best practice to use GitHub’s URLs as package paths for external packages to avoid conflicts.

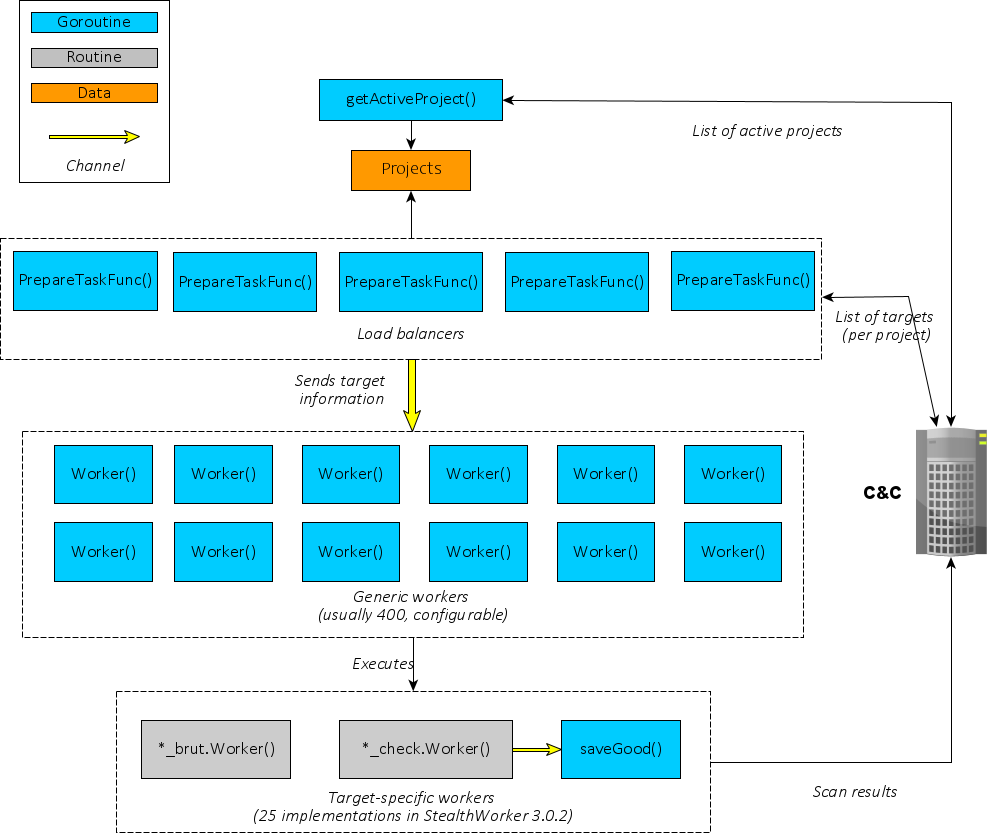

Concurrent Design

In this blog, we will not dig into each StealthWorker’s packages implementation, as it has been already been done several times. Rather, we will focus on the concurrent design made to organize the work between these packages.

Let’s start with an overview of StealthWorker’s architecture:

At first, a goroutine executing getActiveProject() regularly retrieves a list of “projects” from the C&C server. Each project is identified by a keyword (wpChk for WordPress checker, ssh_b for SSH brute-forcer, etc).

From there, the real concurrent work begins: five goroutines executing PrepareTaskFunc() retrieve a list of targets for each project, and then distribute work to “Workers”. There are several interesting quirks here:

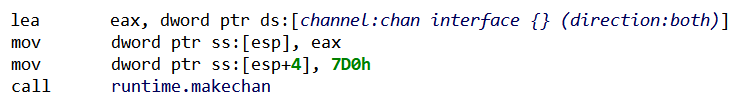

- To allow

PrepareTaskFunc()goroutines to communicate withWorker()goroutines, a Channel is instantiated:

As can be seen from the channel type descriptor — parsed and renamed by the script –, the Channel is made for objects of type interface {}, the empty interface. In others words, objects of any type can be sent and received through it (because “direction:both”).

PrepareTaskFunc() will then receive from the C&C server a list of targets for a given project — as JSON objects –, and for each target will instantiate a specific structure. We already noticed these structures when looking at main package’s routines, here are their reconstructed form in the script’s logs:

> struct main.StandartBrut (4 fields):

- string Host (offset:0)

- string Login (offset:8)

- string Password (offset:10)

- string Worker (offset:18)

> struct main.StandartChecker (5 fields):

- string Host (offset:0)

- string Subdomains (offset:8)

- string Subfolder (offset:10)

- string Port (offset:18)

- string Worker (offset:20)

> struct main.WPBrut (5 fields):

- string Host (offset:0)

- string Login (offset:8)

- string Password (offset:10)

- string Worker (offset:18)

- int XmlRpc (offset:20)

> struct main.StandartBackup (7 fields):

- string Host (offset:0)

- string Subdomains (offset:8)

- string Subfolder (offset:10)

- string Port (offset:18)

- string FileName (offset:20)

- string Worker (offset:28)

- int64 SLimit (offset:30)

> struct main.WpMagOcartType (5 fields):

- string Host (offset:0)

- string Login (offset:8)

- string Password (offset:10)

- string Worker (offset:18)

- string Email (offset:20)

> struct main.StandartAdminFinder (6 fields):

- string Host (offset:0)

- string Subdomains (offset:8)

- string Subfolder (offset:10)

- string Port (offset:18)

- string FileName (offset:20)

- string Worker (offset:28)

> struct main.WPChecker (6 fields):

- string Host (offset:0)

- string Subdomains (offset:8)

- string Subfolder (offset:10)

- string Port (offset:18)

- string Worker (offset:20)

- int Logins (offset:28)Note that all structures have Worker and Host fields. The structure (one per target) will then be sent through the channel.

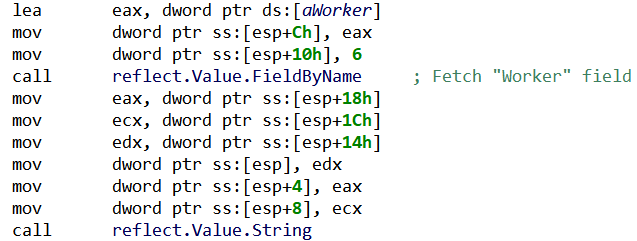

- On the other side of the channel, a

Worker()goroutine will fetch the structure, and use reflection to generically process it (i.e. without knowing a priori which structure was sent):

Finally, depending on the value in Worker field, the corresponding worker’s code will be executed. There are two types of workers: brute-forcing workers, which try to login into the target through a known web platform, and checking workers, which test the existence of a certain web platform on the target.

From a design point-of-view, there is a difference between the two types of workers: checking workers internally relies on another Channel, in which the results are going to be written, and fetched by another goroutine named saveGood(), which reports to the C&C. On the other hand, brute-forcing workers do their task and directly report to the C&C server.

- Interestingly, the maximum number of

Worker()goroutines can be configured by giving a parameter to the executable (preceded by the argumentdev). According to the update mechanism, it seems that the usual value for this maximum is 400. Then, the previously mentioned SizedWaitGroup package serves to ensure the number of goroutines stay below this value:

SizeWaitGroup.Add() is blocking when the maximum number of goroutines has been reached. Each main.Worker() will release its slot when terminating.We can imagine that the maximum amount of workers is tuned by StealthWorker’s operators to lower the risk of overloading infected machines (and drawing attention).

There are two additional goroutines, respectively executing routines KnockKnock() and CheckUpdate(). Both of them simply run specific tasks concurrently (and infinitely): the former sends a “ping” message to the C&C server, while the latter asks for an updated binary to execute.

What’s Next? Decompilation!

The provided Python script should allow users to properly analyze Linux and Windows Golang executables with JEB. It should also be a good example of what can be done with JEB API to handle “exotic” native platforms.

Regarding Golang reverse engineering, for now we remained at disassembler level, but decompiling Golang native code to clean pseudo-C is clearly a reachable goal for JEB. There are a few important steps to implement first, like properly handling Golang stack-only calling convention (with multiple return values), or generating type libraries for Golang runtime.

So… stay tuned for more Golang reverse engineering!

As usual, if you have questions, comments or suggestions, feel free to:

- leave a comment on this post

- email support@pnfsoftware.com

- message us on Slack

- or send us a Tweet @jebdec

References

A few interesting reading for reverse engineers wanting to dig into Golang’s internals:

- https://rednaga.io/2016/09/21/reversing_go_binaries_like_a_pro/

- https://2016.zeronights.ru/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/GO_Zaytsev.pdf

- https://go-re.tk

- https://blog.stalkr.net/2015/04/golang-data-races-to-break-memory-safety.html

- https://cmc.gitbook.io/go-internals/

- http://home.in.tum.de/~engelke/pubs/1709-ma.pdf

- https://science.raphael.poss.name/go-calling-convention-x86-64.html

- The Golang compiler was originally inherited from Plan9 and was written in C, in order to solve the bootstrapping problem (how to compile a new language?), and also to “easily” implement segmented stacks — the original way of dealing with goroutines stack. The process of translating the original C compiler to Golang for release 1.5 has been described in details here and here. ↩

- There are alternate compilers, e.g. gccgo and a gollvm ↩

- Golang also allows to compile ‘modules’, which can be loaded dynamically. Nevertheless, for malware writers statically-linked executables remain the usual choice. ↩

- Readers interested in the internals of JEB disassembler engine should refer to our recent REcon presentation ↩