In part 1 of this series, we gave an overview of the Intermediate Representation used by JEB’s Native Analysis Pipeline, as well as a simple Python script demonstrating how to use the API to access and print out IR-CFG of decompiled routines.

In part 2, we continue our exploration of JEB IR. We will show how to write a custom IR optimizer plugin to clean-up a custom obfuscation used in a piece of code. The resulting decompiled C code will end up very readable as well.

Before you proceed, make sure to update JEB Pro to version 3.1.1+.

Obfuscated Crypto-stealer Code

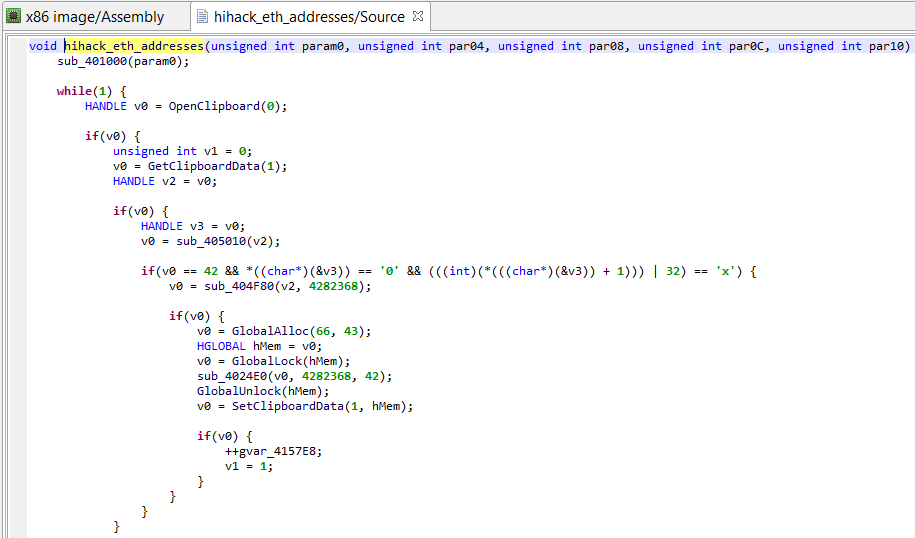

The sample we are going to look at monitors Windows clipboards for cryptocurrency-looking wallet addresses, and replaces them with a desired target address. The sample is specifically targeting Ethereum wallet addresses. It is a neutered final stage payload – the recipient address has been scrambled to render the code ineffective.

Although the payload is unpacked, what is interesting is that one of its key routines is obfuscated: custom garbage code was inserted.

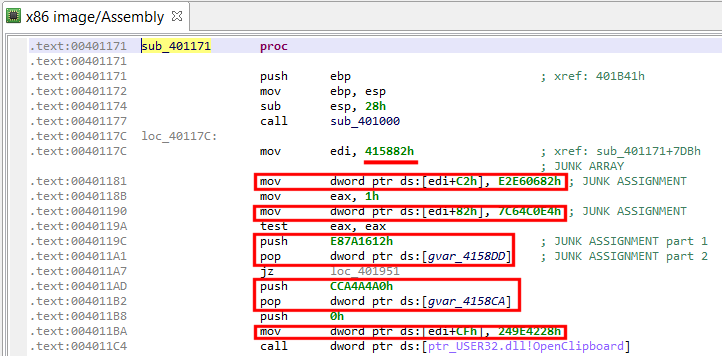

The garbage code is easy to go through: a bit of manual analysis shows that junk instructions are assigning pseudo-random values to an array whose bytes are never used. Two types of assembly patterns are present:

1- mov dword ptr [edi + offset], junk_value ; edi previously init. to

; junkarray address

2- push junk_value

pop dword ptr [junkarray_address + offset]

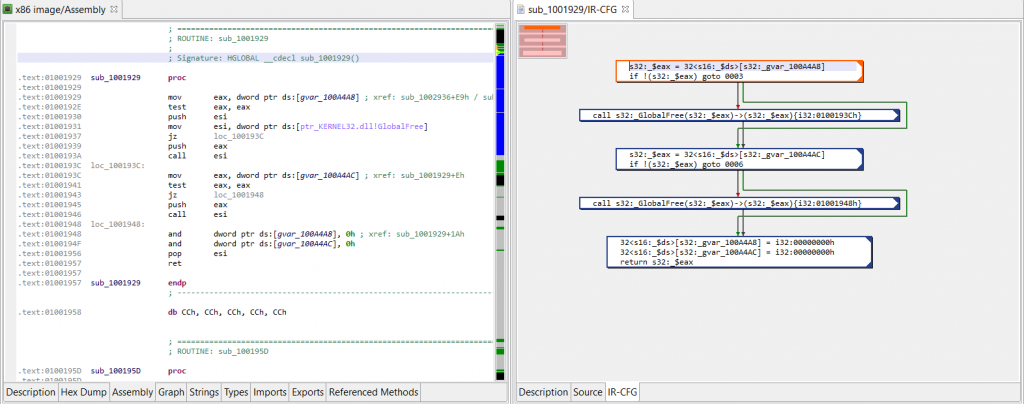

If we decompile that code and look at the final IR (as shown below), we can see that those instructions ended up being converted and optimized to the following type of assignment:

Assign(Mem(mem_address), Imm(junk_value))

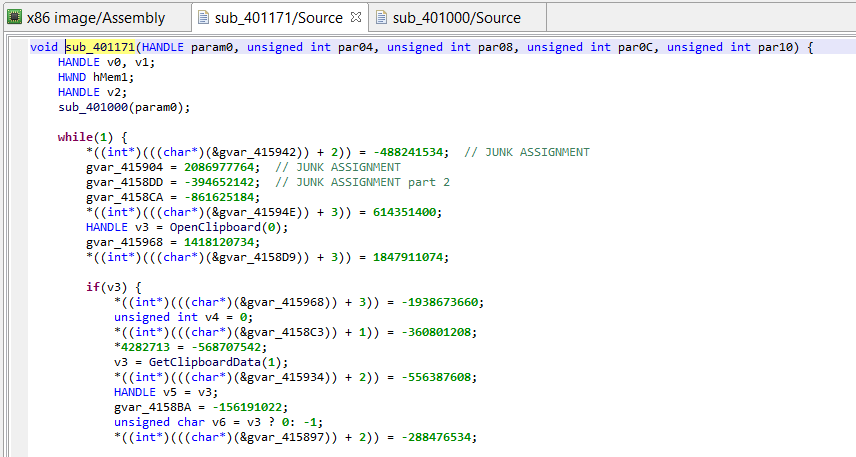

Currently, the decompiled code looks like the following, hard-to-digest blob:

Although quite painful to read, we can follow the program’s logic by abstracting away the junk assignments. (Essentially, win32 functions’ OpenClipboard, GetClipboardData, and SetClipboardData are used to retrieve, check, and replace copy-pasted Ascii and Unicode text, if they match the following pattern “/0x(..){20}/”. The replacement string target wallet address, previously decrypted by sub_401000.)

Cleaning the Intermediate Representation

Recall that the native analysis pipeline can be simplifed as the workflow below:

CodeObject (*)

-> Reconstructed Routines & Data

-> Conversion to IR (low-level, non-optimized)

-> IR Optimizations <--- this is where we'll work

-> Final IR (higher-level, optimized, typed)

-> Generation of AST

-> AST Optimizations

-> Final AST (final, cleaned)

-> High-level output (eg, C variant)

Our custom IR optimizer will look for junk assignments and remove them. The important criteria are: What is the junk array start and end addresses? Is it common to all routines in the binary, or is there one array per routine? Those questions may be hard to answer in the general case. However, for our specific sample file, we can assert with a high-degree of certainty that the junk array:

– starts at address 0x415882

– is at most 256 bytes long

– is used solely by sub_401171, the routine we want to analyze

Because of the above restrictions, the IR optimizer we are going to write should be qualified as a custom or ad-hoc IR optimizer. Chances are, we won’t be able to reuse it as-is in other programs without some amount of tweaking.

Let’s get started, we will:

– create an Eclipse project with scaffold code for a Java back-end plugin

– write and test a custom IR optimizer with a headless client

– deploy the plugin and make it usable and accessible from the UI desktop client

Creating a Plugin Project

Before we proceed, make sure to:

- Define an environment variable JEB_HOME, that points to your JEB installation folder

- Install Eclipse IDE

Then:

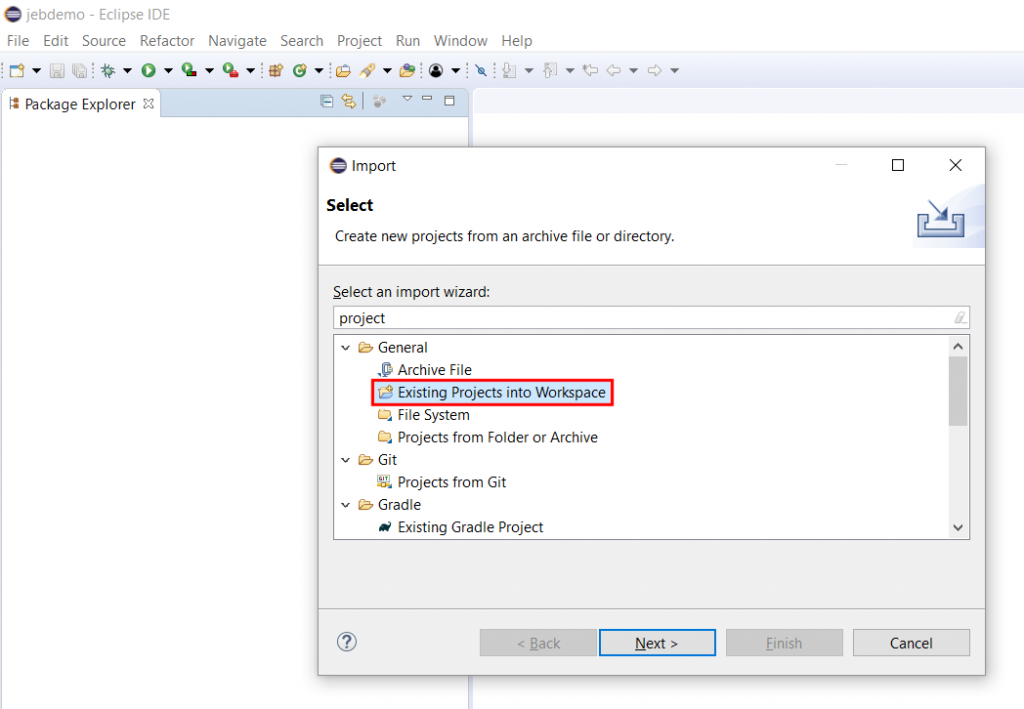

- Clone the jeb-native-ir-optimizer-example1 repository.

- Create an Eclipse project by running:

- On Windows: create-eclipse-project.cmd

- On Linux/macOS: create-eclipse-project.sh

- Open Eclipse and import the newly-created project into your Workspace (File, Import, Existing Projects into the Workspace, select the cloned repository folder, proceed)

Debugging the Obfuscation

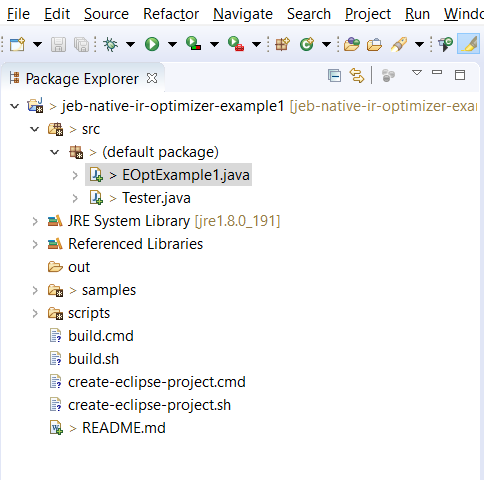

Now that your project is imported in Eclipse, you should be able to see two source files in src’s default package:

- Tester.java

- EOptExample1.java

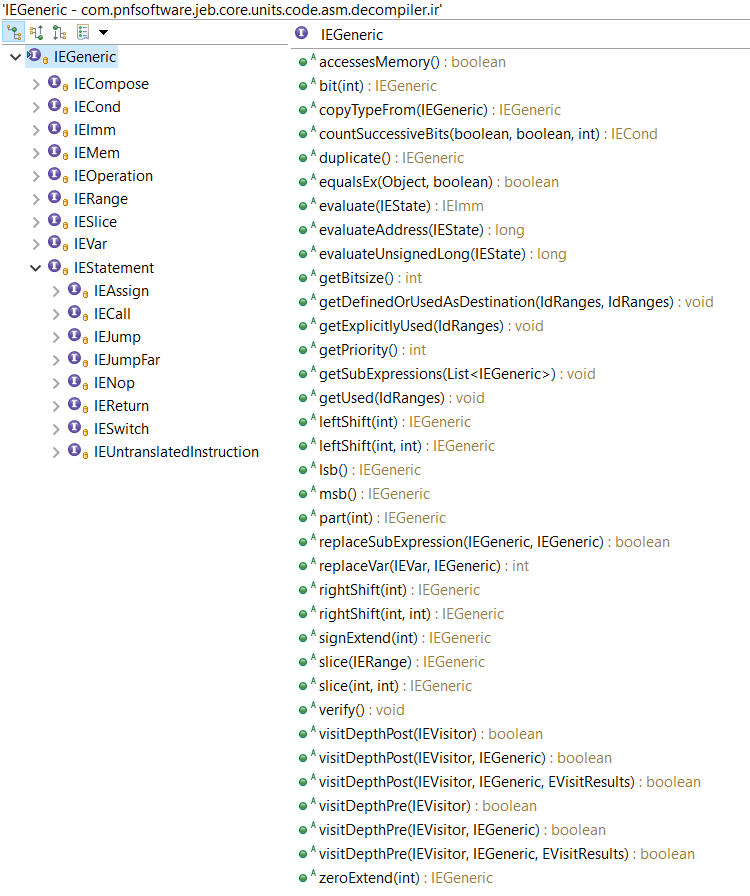

EOptExample1 is the IR optimizer plugin we will be working on. (Note that several classes of plugins exist, this one is a native IR optimizer, and therefore inherits from AbstractEOptimizer or one its subclasses.)

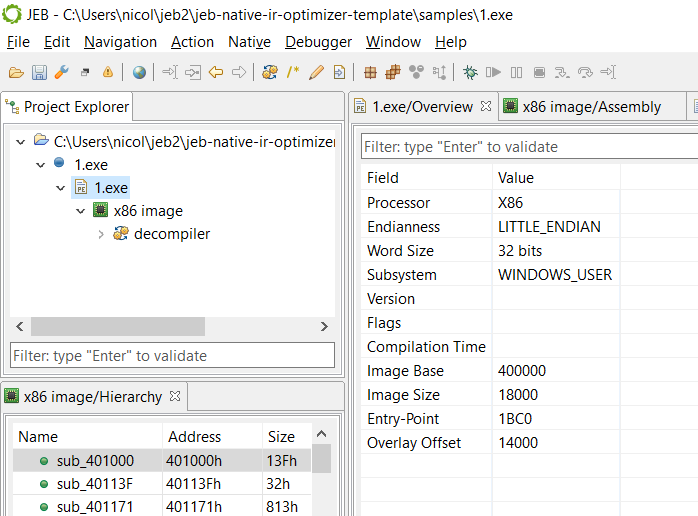

Tester creates a headless JEB instance that loads the plugin EOptExample1.

Tester.java does the following:

- Create a JEB instance 1

- Load the test plugin EOptExample1

- Then, create a JEB project and load the artifact file samples/1.exe (IMPORTANT: unzip 1.zip to 1.exe first – password: password)

- Analyze the artifact

- Retrieve a handle on the native decompiler

- Retrieve a handle on the to-be-analyzed routine sub_401171

- Perform a full decompilation of that routine

Let’s have a preliminary look at EOptExample1: This IR optimizer type is set to STANDARD, which is not ideal when you use custom optimizers tailored for specific code. A better IR optimizer class for those is ON_DEMAND: those optimizers are to be manually invoked, e.g. from JEB UI (menu: File, Advanced Unit Options). However, during development, since we are focusing on a particular file and routine, STANDARD type may be fine. Standard optimizers are called during regular IR optimization phases of the decompilation pipeline.

public class EOptExample1 extends AbstractEOptimizer {

public EOptExample1() {

super(DataChainsUpdatePolicy.UPDATE_IF_OPTIMIZED);

getPluginInformation().setName("Sample IR Optimizer #1");

getPluginInformation().setDescription("Remove IR-statements reduced to \"*(&garbage + delta) = xxx\"");

getPluginInformation().setVersion(Version.create(1, 0, 0));

// Standard optimizers are normally run, as part of the IR optimization stages in the decompilation pipeline

setType(OptimizerType.STANDARD);

}

// replace all IR statements previously reduced to EMem ("[junk_address] = xxx") to ENop

@Override

public int perform(boolean updateDFA) {

logger.info("IR-CFG before running custom optimizer \"%s\":\n%s", getName(),

DecompilerUtil.formatIRCFGWithContext(2, cfg, ectx));

// ...

// optimizer code

}

}

Note the plugin’s data-chains update policy, set to UPDATE_IF_OPTIMIZED. Optimizations that specify this flag tell their runner, aka the master optimizer that orchestrate them, that identifiers may be modified – hence, if optimizations occurred, a data flow analysis (DFA) pass needs to take place again. DFA update policies are a topic for another article.

Lines 3-5 are plugin metadata information, such as name and description, authorship, version numbers (including minimum/maximum JEB back-end versions), etc.

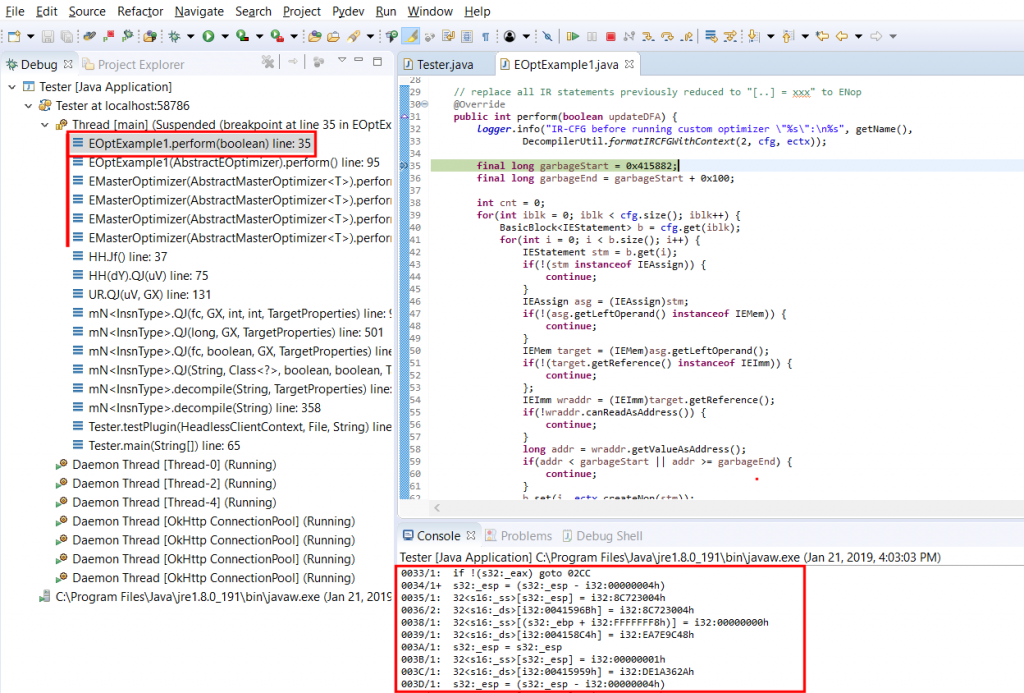

Before we deep-dive into perform(), let’s first set a breakpoint on line 15, where logger.info(…) is called. Then, start a debugging session for Tester: menu Run, command Debug (hotkey: F11.)

After a few seconds of analysis, your breakpoint should be hit; it corresponds to the first-time invocation of your custom optimizer. The logger prints out the IR-CFG that’s about to be optimized. Let’s have a look at it:

IR-CFG before running custom optimizer "Sample IR Optimizer #1":

>> IN(@0): ecx={@D} esp={@0} ebp={@1} ss={@1,@C,@18,@1D,@21,@24,@25,@27,@30,@35,@38,@3B,@3E,@3F,@41,@43,@46,@4F,@51,@54,@56,@59,@5C,@5D,@5F,@6B,@77,@81,@84,@9B,@9E,@A0,@AC,@B8,@BA,@BD,@BF,@C3,@C5,@C7,@CB,@CD,@D1,@D2,@D4,@E0,@E9,@EF,@F1,@F5,@F7,@FB,@FC,@FE,@100,@103,@106,@107,@109,@10C,@10E,@112,@114,@116,@11A,@11C,@11F,@122,@123,@12E,@131,@133,@137,@139,@13D,@13E,@140,@143,@145,@149,@14B,@14F,@150,@152,@15D,@173,@176,@179,@17C,@17D,@17F,@181,@18A,@18C,@18F,@191,@194,@196,@19A,@19D,@19E,@1A0,@1B3,@1BF,@1C2,@1D9,@1DC,@1E0,@1EC,@1EF,@1F1,@1F3,@1F7,@1F9,@1FC,@1FF,@202,@203,@205,@211,@21D,@220,@222,@226,@227,@229,@22B,@22E,@231,@232,@234,@237,@23A,@23C,@23E,@242,@244,@246,@24A,@24C,@250,@251,@25C,@25F,@262,@263,@265,@268,@26A,@26E,@271,@272,@27A,@27F,@295,@298,@29A,@29D,@2A4,@2A9,@2AD,@2B0,@2B2,@2B6,@2B7,@2BA,@2BC,@2C0,@2C2,@2C6,@2C7,@2CA,@2CD,@2D2,@2DE,@2E4,@2E7,@2E8,@2EA} ds={@F,@11,@19,@1E,@22,@28,@31,@36,@39,@3C,@40,@44,@4C,@4E,@52,@55,@57,@5A,@60,@6C,@74,@78,@7B,@82,@85,@86,@87,@8E,@90,@92,@9C,@A1,@A3,@A4,@AD,@B5,@B7,@BB,@C0,@C4,@C8,@CE,@D5,@E1,@EA,@ED,@F2,@F8,@FD,@FF,@101,@104,@10A,@10F,@113,@117,@11B,@11D,@120,@124,@12F,@134,@13A,@13F,@141,@146,@14C,@153,@15A,@15C,@163,@165,@166,@167,@170,@171,@174,@177,@17A,@17E,@180,@187,@189,@18D,@192,@197,@19B,@1A1,@1AB,@1B4,@1B7,@1B9,@1C0,@1C3,@1C4,@1C5,@1CC,@1CE,@1D0,@1DA,@1DD,@1DE,@1E1,@1E9,@1ED,@1F0,@1F4,@1FA,@1FD,@200,@206,@212,@219,@21B,@21E,@223,@228,@22A,@22C,@22F,@235,@238,@23B,@23F,@243,@247,@24D,@252,@25B,@25D,@260,@264,@266,@26B,@26F,@273,@27B,@27E,@285,@287,@288,@289,@292,@293,@296,@29B,@2A5,@2AA,@2AE,@2B3,@2B8,@2BD,@2C3,@2C8,@2CE,@2D0,@2D3,@2DF,@2E1,@2E2,@2E5,@2EB} OpenClipboard={@25} GetClipboardData={@3F,@17D} GlobalAlloc={@FC,@227} GlobalLock={@107,@232} GlobalUnlock={@13E,@263} SetClipboardData={@150,@272,@2B7,@2C7} CloseClipboard={@2CB} Sleep={@2E8} sub_401000={@D} sub_405010={@5D} sub_404F80={@D2} sub_4024E0={@123,@251} sub_404E54={@19E} sub_404E14={@203}

0000/1> s32:_esp = (s32:_esp - i32:00000004h) DU: esp={@1,@2,@B} | UD: esp={}

0001/1: 32<s16:_ss>[s32:_esp] = s32:_ebp DU: | UD: esp={@0} ebp={} ss={}

0002/9: s32:_ebp = s32:_esp DU: ebp={@38,@41,@46,@4F,@54,@56,@84,@9E,@B8,@BD,@C5,@FE,@100,@10C,@114,@11C,@131,@140,@15D,@176,@17F,@181,@18A,@18F,@194,@1C2,@1DC,@1EF,@1F1,@1FC,@229,@22B,@237,@23C,@244,@25C,@265,@27F,@298,@29D} | UD: esp={@0}

000B/1: s32:_esp = (s32:_esp - i32:0000002Ch) DU: esp={@C,@D,@17} | UD: esp={@0}

000C/1: 32<s16:_ss>[s32:_esp] = i32:0040117Ch DU: | UD: esp={@B} ss={}

000D/1: call s32:_sub_401000(s32:_ecx)->(s32:_eax){32[s32:_esp]} DU: eax={} | UD: ecx={} esp={@B} sub_401000={}

000E/1+ s32:_edi = i32:00415882h DU: edi={} | UD:

000F/1: 32<s16:_ds>[i32:00415944h] = i32:E2E60682h DU: | UD: ds={}

0010/1: s32:_eax = i32:00000001h DU: eax={} | UD:

0011/6: 32<s16:_ds>[i32:00415904h] = i32:7C64C0E4h DU: | UD: ds={}

0017/1: s32:_esp = (s32:_esp - i32:00000004h) DU: esp={@18,@1A} | UD: esp={@B,@2EC}

0018/1: 32<s16:_ss>[s32:_esp] = i32:E87A1612h DU: | UD: esp={@17} ss={}

0019/1: 32<s16:_ds>[i32:004158DDh] = i32:E87A1612h DU: | UD: ds={}

001A/1: s32:_esp = (s32:_esp + i32:00000004h) DU: esp={@1C} | UD: esp={@17}

001B/1: nop DU: | UD:

001C/1+ s32:_esp = (s32:_esp - i32:00000004h) DU: esp={@1D,@20} | UD: esp={@1A}

001D/1: 32<s16:_ss>[s32:_esp] = i32:CCA4A4A0h DU: | UD: esp={@1C} ss={}

001E/2: 32<s16:_ds>[i32:004158CAh] = i32:CCA4A4A0h DU: | UD: ds={}

0020/1: s32:_esp = s32:_esp DU: esp={@21,@23} | UD: esp={@1C}

0021/1: 32<s16:_ss>[s32:_esp] = i32:00000000h DU: | UD: esp={@20} ss={}

0022/1: 32<s16:_ds>[i32:00415951h] = i32:249E4228h DU: | UD: ds={}

0023/1: s32:_esp = (s32:_esp - i32:00000004h) DU: esp={@24,@25,@26} | UD: esp={@20}

0024/1: 32<s16:_ss>[s32:_esp] = i32:004011CAh DU: | UD: esp={@23} ss={}

0025/1: call s32:_OpenClipboard(32<s16:_ss>[(s32:_esp + i32:00000004h)])->(s32:_eax){32[s32:_esp]} DU: eax={@33} | UD: esp={@23} ss={} OpenClipboard={}

...

... (trimmed)

...

The above IR listing is a human-friendly representation of IR statements. The general format of this listing is:

cnt what

1 >> IN(@EntryOffset){live_inputs}

1* offset/lengthC <insn> | DU:<def-use-chains> UD:<use-def-chains>

0+ << OUT(@ExitOffset){reaching_outputs}

- offset: IR statement offset

- length: IR statement length (generally, 1)

- C: indicates whether the instruction is

- the entry-point instruction (>)

- the first of a basic-block (+)

- any other instruction (:)

- insn: IR statement instruction (refer to Part 1 of this blog series)

- DU/UD: routine def-use and use-def chains

- IN: live input variables at the entry-point

- OUT: reaching output variables at a given exit point

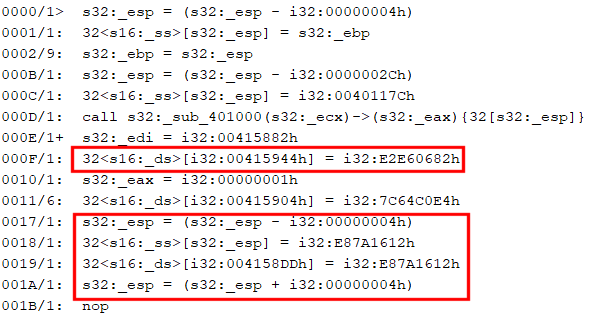

The IR listing is relatively readable, although quite verbose at this early stage of optimization (roughly, the first pass in tier 1 of the analysis pipeline). The important idioms to look at here are:

a/ The first one is an Assign(Mem(Imm), Imm), which corresponds to optimized “mov [edi + offset], value”, where the value of edi was determined, propagated further, and the addition folded and converted to an immediate address.

b/ The second one is a partially optimized “push value / pop [address]”. Later optimizations phases will find and remove esp updates or esp-based operations, as was shown in the pseudo-code earlier. What we need to focus on here is the Assign(Mem(Imm), Imm), like the one in a/.

Those are the bits we will look for and modify: Assuming those assignments are useless, we will simply replace them by Nop statements.

Writing the Optimizer

At this point, our preliminary understanding of the obfuscation is enough to start writing the clean-up optimizer. Its code is extremely simple, for two main reasons:

– The obfuscation scheme itself is relatively trivial

– Other built-in JEB optimizers are giving us clean IR assignments to work on

Let’s look at the code of proceed():

@Override

public int perform(boolean updateDFA) {

final long garbageStart = 0x415882;

final long garbageEnd = garbageStart + 0x100;

int cnt = 0;

for(int iblk = 0; iblk < cfg.size(); iblk++) {

BasicBlock<IEStatement> b = cfg.get(iblk);

for(int i = 0; i < b.size(); i++) {

IEStatement stm = b.get(i);

if(!(stm instanceof IEAssign)) {

continue;

}

IEAssign asg = (IEAssign)stm;

if(!(asg.getLeftOperand() instanceof IEMem)) {

continue;

}

IEMem target = (IEMem)asg.getLeftOperand();

if(!(target.getReference() instanceof IEImm)) {

continue;

};

IEImm wraddr = (IEImm)target.getReference();

if(!wraddr.canReadAsAddress()) {

continue;

}

long addr = wraddr.getValueAsAddress();

if(addr < garbageStart || addr >= garbageEnd) {

continue;

}

b.set(i, ectx.createNop(stm));

cnt++;

}

}

return postPerform(updateDFA, cnt);

}

This optimizer inherits from AbstractEOptimizer. Therefore, the perform() method works on an IR-CFG. (Not all optimizers may choose to do so; it is sometimes easier to work directly on statements or expressions.)

process() goes through all statements or every basic block of the IR-CFG. Using the instanceof operator, we check that the statement is an assignment such as: Mem(address) = Imm. The address is retrieved, and we make sure that it falls within the junk array. If those checks succeed, we replace the assignment by a Nop.

And that is it. Clean and simple – although, not quite portable, since the junk array address and size are hard-coded into the code! But that is not the point of this blog, and neither is portability a first-class goal when writing optimizers for custom code.

Next up, let’s see how to use the plugin in an interactive session using the desktop client.

Building, Deploying, Interactive Use

In order to use the optimizer within the JEB desktop client, we either:

- Register the plugin as a development plugin;

- Or build the plugin as a Jar and drop it in JEB’s coreplugins/ folder.

Development Plugin

This is the easiest option. You may consider it as an intermediate step between prototyping with the headless client, as demonstrated above, and a full-blown, deployed Jar plugin.

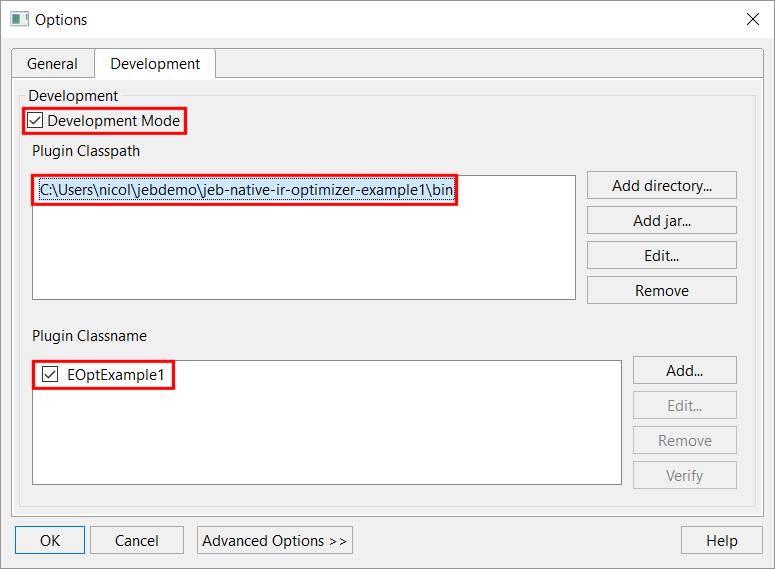

Open the Options panel, Development tab, tick the option “Development Mode”, add the bin/ folder of your plugin’s project to the classpath, and add the classname of your plugin entry-point:

Press OK and restart JEB. Your plugin will be loaded and ready to use. You may now skip to the section “Using the IR optimizer plugin”.

Building a Jar plugin

The alternative is to run build.cmd (on Windows) or build.sh (on Linux/macOs), which calls an Ant script in the scripts/ folder, therefore, make sure to have Ant installed on your system first. You may also customize the plugin name and version before building.

The resulting Jar plugin file will be generated in your project’s out/ folder. Copy it to your JEB coreplugins/ folder and start the JEB client. Your plugin will be automatically loaded, along with the other plugins.

Using the IR Optimizer Plugin

If your plugin has the type STANDARD (default), then, as explained earlier, it will be invoked by the optimizations’ orchestrator automatically, at various times during the decompilation pipeline. If that’s the mode you’d like to choose, make sure that your plugin is generic enough to handle all types of input routines, else you’re in for some strange surprises if you ever forget to remove it from your coreplugins/ folder.

An alternative is to convert it to an on-demand plugin:

public EOptExample1() {

super(DataChainsUpdatePolicy.UPDATE_IF_OPTIMIZED);

getPluginInformation().setName("Sample IR Optimizer #1");

getPluginInformation().setDescription("Remove IR-statements reduced to \"*(&garbage + delta) = xxx\"");

getPluginInformation().setVersion(Version.create(1, 0, 0));

// Standard optimizers are normally run, as part of the IR optimization stages in the decompilation pipeline

//setType(OptimizerType.STANDARD);

// alternative (better for production / in UI use):

setType(OptimizerType.ON_DEMAND);

setPreferredExecutionStage(-NativeDecompilationStage.LIFTING_COMPLETED.getId());

setPostProcessingActionFlags(PPA_OPTIMIZATION_PASS_FULL);

}

– Line 11 makes the optimizer on-demand. Users must manually activate it, on specific code.

– Line 12 is recommended for on-demand optimizers: we specify at which point in in the pipeline the plugin should be called.

– Finally, we set some post-processing flags, specifying that a full round of standard optimizations must be performed after our custom optimizer has run: this will allow cleaning up code remnants, and optimize our IR-CFG further – something made possible after running an optimization pass like this one.

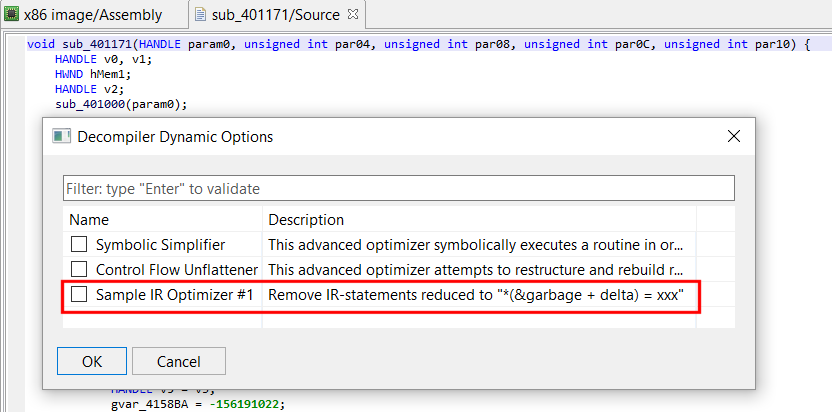

On-demand optimizer plugins show up in the File, Advanced Unit Options dialog box, that you may bring up when a decompiled routine has the focus:

Tick the optimizer box, press OK. The routine will be re-decompiled.

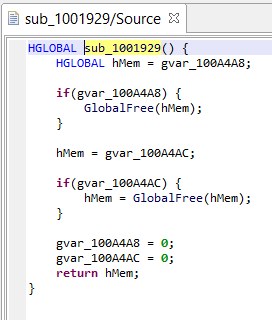

Clean Code

Regardless which method you choose, once cleaned up, the IR will allow for better downstream pipeline phases, including typing, AST generation, AST optimizations, etc.

The pseudo-C code has become quite readable:

Conclusion

That is it for part 2. We scratched the surface of IR optimizers (which themselves are a relatively small – albeit important – part of the overall decompilation pipeline 2) but it’s a good start. I strongly encourage you to experiment and ask your questions on our Slack channel. One ongoing effort right now is to bring the API documentation up to speed in terms of contents and sample code.

In part 3, we will continue exploring IR optimizers. Later on in the series, we will show how to write AST optimizers 3, how to write decompilation modules, and show how existing decompilers can be cutomized further. Stay tuned!

- JEB must have been previously run, at least once: EULA accepted, license key generated, etc. ↩

- The decompilation pipeline is one component of the native analysis pipeline, which is one module, among tens, of the JEB back-end: the public API is worth exploring if you’re into advanced use cases. ↩

- AST generation is one of the very final decompilation phases – working on the syntax tree serves different purposes than working on the IR ↩